Rags to Riches, Kosode to Kimono

Introduction

Uchikake, from Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2022

The kimono is a beautiful piece often seen during Japanese festivals and rented to be tried on by foreign tourists. There are actually many different types of kimonos, meant to be worn for specific occasions or certain people. The “furisode” is the most formal kimono for unmarried women. They are usually worn at coming-of-age ceremonies, “seijin shiki”, and at weddings, for unmarried female relatives of the bride. Married women would wear “tomesode” which have shorter sleeves and the pattern of the kimono would only begin below the waist. “Iromuji” are kimonos generally worn for tea ceremonies while “mofuku” are black kimonos for mourning (Obradovic, 2021). The commonly known “yukata” is meant to be worn at home like pajamas or informally during the summer (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1919). “Kimono” means “thing to wear or thing to be worn”, however, the garment has gone through periods of existing as a simple clothing item to existing as an art form. To understand the beauty of a kimono, we need to take a look into its past and the ways the kimono has changed over time. This biography will explore how the design of the kimono began from an inner robe (“kosode”), the production process of creating a kimono, innovations in decorative techniques, and the symbolism and motifs that artisans wove into their kimono patterns.

History

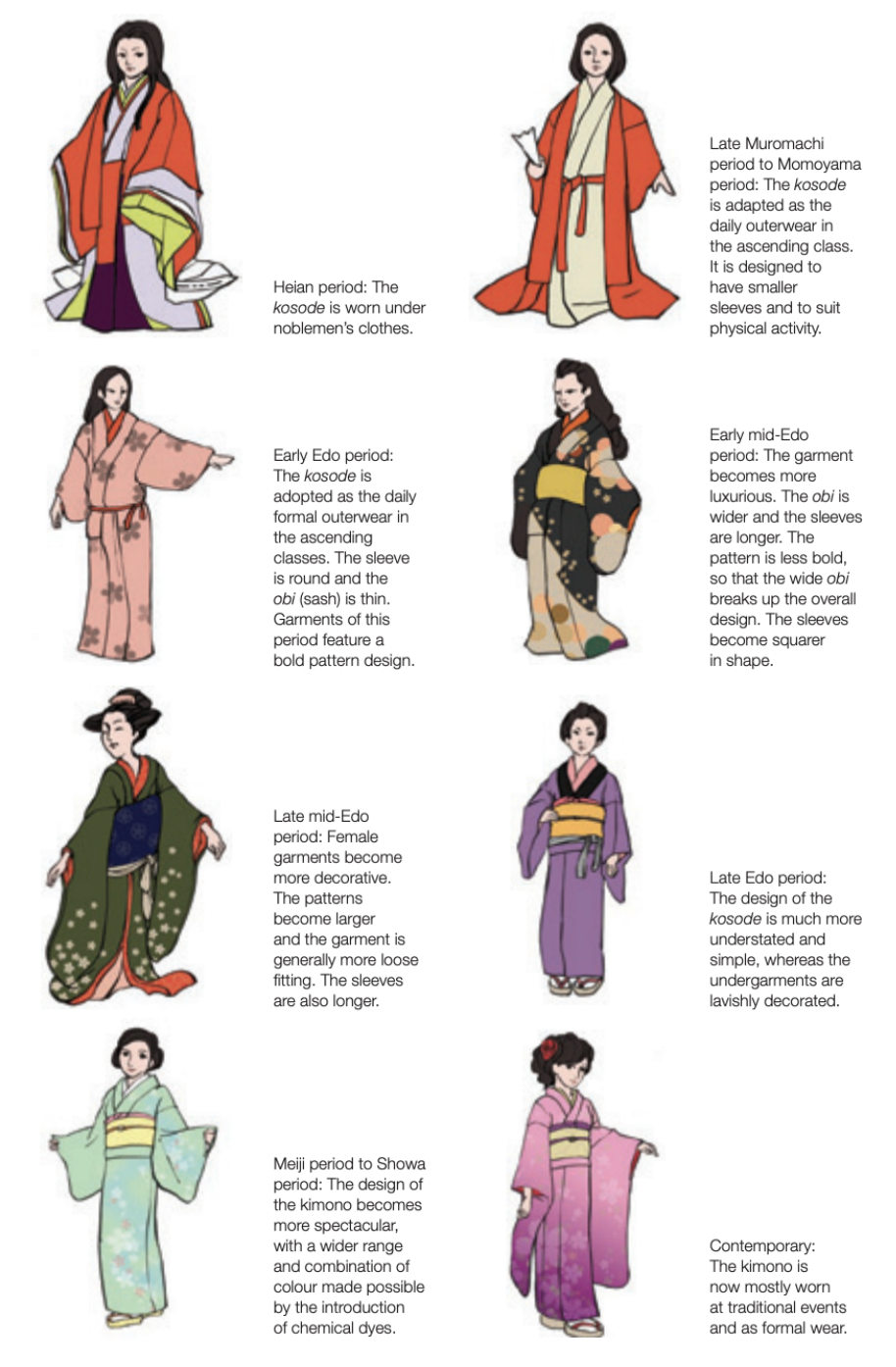

The traditional Japanese kimono first appeared in the Heian Period (794-1185 CE), developing from pieces influenced by Chinese fashion such as the “hanfu” (The History of Japanese Kimono Clothing, 2019). The garments of aristocrats consisted of an outer coat, or “oosode” (大袖, big sleeves), an inner layer, or “kosode” (小袖, small sleeves), and loose trousers, or “hakama”. Noblewomen wore a formal court dress called “jūnihitoe” which consisted of 12 different layers and noblemen wore “sokutai” (The Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts, 2022). The kosode began to be worn without hakama in the Muromachi Period (1336-1573 CE) and an “obi”, or belt, was used to tie the kosode at the waist instead. It was adopted as the formal outerwear among samurai because its smaller sleeves were more practical for physical movement. The kosode then became clothing that common people could wear and not just nobility (Mori, M., & Dickens, P., 2012). By the Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568-1600 CE), all the current features of a kimono were present. Decorative designs were added to the previously plain inner robes and techniques of weaving and dyeing the kosode accelerated. Reaching the Edo Period (1603–1867 CE), and particularly the Genroku period (1688–1704 CE), the development of art forms flourished due to the rising status of the merchant class (The Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts, 2022). The Genroku culture was characterized by displays of wealth and increased patronage of the arts by these wealthy merchants. This arose from the peace that came with the fifth Tokugawa shogun’s rule, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1680-1709), which led to increases in literacy within cities, agricultural productivity, and urban area development, therefore, increasing demand for goods (Britannica, 1998) (Genroku Period, 2022). Changes to the kosode included longer sleeves for unmarried women and designs were characterized by asymmetry and large patterns (Polyzoidou, 2021). Finally, in the Meiji Period (1868–1912), the social class system of samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants was abolished and the kosode was renamed “kimono”. Western culture was introduced to Japan at this time, and the Japanese government, as well as Japanese men, adopted western clothing while Japanese women were encouraged to continue wearing kimonos (Green, 2021).

Process of Creation

Now that we have an idea of the historical context of the kimono, we can start to look at how the kimono was made and what it looked like. Kimonos are made from single rolls of cloth, called “tanmono”, that are about 36 centimeters wide by 11.5 meters long for women, and 40 centimeters wide by 12.5 for men (Tsumugi, 2019). The cloth is cut into eight parts (two sleeves, front body part, back body part, two overlaps, a neckband or color, and “okumi” or narrow panels at the front of the kimono) (The Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts, 2022) (see Appendix B). These cuts are made with only straight lines, unlike Western clothing which is made using curved and straight edges (NHK World, 2015). Due to the simplicity of constructing the kimono, many households in rural areas of the Edo period had their own loom and women held the role of sewing and weaving together the kimono. The silk kimono, however, required “skills of specialist artisans, the majority of whom were men” (Victoria and Albert Museum, 2016).

The overall manufacturing process of the kimono consisted of the division of labor and complex networks of different craftspeople working on the product. These included “spinners, weavers, dyers, embroiderers, specialist thread suppliers, stencil makers, designers”, weaving masters (“orimoto”), as well as salesmen or wholesalers (“tonya”) (Moon, 2013). A simplified version of the flow between these groups can be seen in Appendix C. Each step of the process was usually “carried out by small-scale independent family businesses generation after generation” rather than a combined factory production (Moon, 2013). In addition, the orimoto directed the entire process and served as the source of communication between groups of artisans. Once the kimono was created, the garments were sent to tonya who would sell the kimono to retail shops along with kimono accessories. This produced a hierarchical system between the masters, the craftsmen, and the wholesalers (tonya) (Moon, 2013).

Silk Production

Starting from the earliest stage of the process, kimono-making begins with silk production. Before silk factories appeared in the Meiji era, the women of silk farm households were responsible for taking care of silkworms while the men supervised (Morris-Suzuki, 1992). The tasks of feeding the silkworms, hatching them from their cocoons, turning the cocoons into silk thread that is reeled onto a hand spindle, spinning the silk on a loom, and finally, weaving cloth from the silk can be seen in images 1 through 12 of Appendix D. The tools used in silk production can be inferred by matching the images of Appendix E to the previous prints made by Utamaro. The two images on the top left of Appendix E are likely a hand-turned spindle on the far left and a heedle that would be used in No 9. of Appendix D. The second image on the bottom resembles the wheel being used in No 11. of Utamaro’s series. The third image on the top of Appendix E looks like one of the processes of moving the silkworms or inspecting the cocoons, similar to No 4. of Appendix D. The third image on the bottom of Appendix E seems similar to the basket of mulberry leaves being sorted in No 3. of Appendix D.

Kimono Pattern-Making Techniques

Nishijin-Ori

Once the silk was created, various materials and techniques of weaving could be used to create the kimono cloths. These included Rinzu (figured satin silk), Shusu (satin silk), Chirimen (plain weave crepe silk), Yuzen (freehand paste-resist dyeing), Kaki-E (Ink Painting), Suri-Hitta (stencil imitation tie-dyeing), Shibori (tie-dyeing), Kawari-Aya (broken twill silk), and Itajime (block-clamp resist dyeing) (History of Kimono, 2022). Focusing on the more well-documented methods of Nishijin-Ori and Yuzen, we can see the innovation that occurred in Japanese cloth-making. Nishijin-ori or Nishijin brocade was hand-woven silk produced in Nishijin (part of Kyoto) from as early as the 5th or 6th century but it became known as Nishijin-ori in the 15th century (Morris-Suzuki, 1992). This practice used threads that were dyed before weaving rather than dying the threads after they were woven together. Nishijin-ori required the designer to plan out and draw the design onto grid sheet-like paper before doing anything else. The design map was then used to weave the pattern into the fabric by punching holes onto pattern paper (“monshi”). Next, threads would be twisted together to create varying thicknesses, refined by removing the animal protein to keep the thread white, and dyed the colors of the design pattern. Afterward, the threads would be wrapped onto a reel and set on a loom (second image on the bottom left of Appendix E) to then be put through a heddle (second image on the top left of Appendix E) which would separate and divide the threads. The process could finish once the weaving was completed on the loom for some fabrics, such as ones used for an obi, or a finishing process took place for other textiles, such as ones used to make kimonos (Koge Japan, 2022).

Kyo-Yuzen

The second technique of yuzen-dyeing, or Kyo-yuzen, was originally named after Miyazaki Yuzensai, a fan designer. The technique was developed in 1683 after the Edo shogunate issued sumptuary laws as an attempt to maintain distinctions between social classes. The Tokugawa government was displeased with the merchant class growing wealthier, and had decreed that merchants were stepping out of place by dressing in fine silks: “It is distressing to see a merchant wearing good silks. Pongee suits him better and looks better on him. But fine clothes are essential to a samurai's status, and therefore even a samurai who is without attendants should not dress like an ordinary person” (Shively, 1964). These regulations prohibited luxurious costumes that used purple or red fabric, gold embroidery, or intricately dyed shibori patterns so people looked for ways to decorate kimonos without using traditional techniques such as embroidery, pasting foil, or tie-dyeing (Mori, M., & Dickens, P., 2012). This is how the technique of dyeing cloth was invented. Outlines of designs were drawn with a rice starch paste (“itome nori”) before the dye liquid (“gojiru”) could be brushed onto the cloth. The ratio of glutinous rice powder, rice paste, rice bran, and lime used to make the paste was kept a secret by the craftsmen, a part of their “material imaginary”, and the practice of “yuzen-tome” is passed down from generation to generation (Fukatsu-Fukuoka, 2004). This does not mean, however, that the practice stopped evolving. “Itome gata” was a technique that introduced stencils (“katagami”) to apply the starch outlines rather than hand-piping them (see Appendix G). Following itome gata was “kata itome”, which produced more intricate designs by overlaying multiple stencils on top of each other. In 1879, Hirose Jisuke, a craftsman who, like Chen Diexian, was willing to experiment with his craft, developed a technique for mixing the starch paste and dye together. This allowed makers to dye the design directly into the cloth from the stencil rather than brush-filling an outline (Mori, M., & Dickens, P., 2012). These innovations sped up the process of dyeing kimonos and craftsmen were able to create more precise kimono designs (Fukatsu-Fukuoka, 2004).

Role in Society

The designs and patterns of a kimono were not only created for aesthetic purposes but also functioned as a statement of who the person wearing it was. To keep track of all these different patterns and help customers choose a style, makers used documents called “hinagata bon” (Betty, 1992). Each page of the hinagata bon contained “an outline of the back of a garment [] filled in with a proposed pattern or design” and they functioned similarly to the manuscripts from Eyferth, “Craft Knowledge at the Interface of Written and Oral Cultures” or Tang Ying’s "Twenty Illustrations of the Manufacture of Porcelain" text. The images communicated an idea of how the design would actually look to the customer and written text from the artist such as “the name of the designs, suggested colors, or techniques in which such designs might be executed” helped guide the craftsman who would actually make the design in the cloth (Fashion Books of the Edo Period, 2022). These patterns often symbolize “seasons of the year, particular holidays, festivals, ceremonies, famous episodes or periods in Japanese history, places noted for their scenic beauty, elevated moral qualities or simple wish fulfillment, and literature (Richard, 1990). A clear example is Appendix H, where the design is related to one of the poems in “Hyakunin-Isshu” ("Verses by One Hundred Poets"). Siffert notes these details about the image: “To the right of each design is the name of the poet, with a five-line poem inscribed on each side of the garment. Each design reflects the artist's reaction to the sentiment of the poem, sometimes with a line or phrase from the poem incorporated into the pattern” (Betty, 1992). The use of kanji and artistic interpretations of the poems by the artist clearly display their class and refinement through the kosode design which also reflects on the character of the wearer. Other common motifs were plum blossoms (as seen in Appendix I), pine trees (Appendix J), cranes, and water (Appendix K). These motifs could symbolize many meanings; for example, the plum blossom represents winter but it can also represent resilience or consistency as plum blossoms are able to survive harsh winters (Dobson, 2018). To this day, patterns on kimonos continue to hold symbolic meanings and are often worn paired with the occasion or season.

Conclusion

The kimono has a rich history and has gone through many modifications over time to appeal to the fluctuating desires of ruling social classes. The process of kimono making eventually became more mechanized as Western influence from the Meiji period was adopted and large-scale factories appeared. There are, however, efforts by kimono-makers today to retain the traditional tools and techniques that have been passed down over time (Experience Suginami Tokyo, 2018). The kimono has also gotten the attention of Western artisans and elements of the kimono have found their way into some pieces of modern fashion designers of today.

Works Cited

Betty Y. Siffert. (1992). “Hinagata Bon”: The Art Institute of Chicago Collection of Kimono Pattern Books. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 18(1), 86–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/4101580

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia (1998, July 20). Genroku period. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Genroku-period

Dobson, J. (2018). Making Kimono and Japanese Clothes. Batsford. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/2425662/making-kimono-and-japanese-clothes-pdf (Original work published 2018)

Experience Suginami Tokyo. (2018, November). Interview With Miho Iwata. Experience Suginami Tokyo. https://experience-suginami.tokyo/2017/04/interview-with-miho-iwata/

Fashion Books of the Edo Period. (2022). Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/fashion-books-of-the-edo-period-kyoto-prefectural-library-and-archives/OwXxeSDqD6O5Lw?hl=en

Fukatsu-Fukuoka, Yuko. (2004). The Evolution of Yuzen -dyeing Techniques and Designs after the Meiji Restoration.

Genroku period | Japan Module. (2022). Japan: Places, Images, Times, and Transformations. https://www.japanpitt.pitt.edu/glossary/genroku-period

Green, C. (2021, July 26). The Surprising History of the Kimono. JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/the-surprising-history-of-the-kimono/

History of Kimono. (2022). Yumeya Kimono. https://www.yumeyakimono.com/how-to-wear

Koge Japan. (2022). Nishijin brocade (Nishijin ori). https://kogeijapan.com/locale/en_US/nishijinori/

Moon, O. (2013). Challenges Surrounding the Survival of the Nishijin Silk Weaving Industry in Kyoto, Japan. International Journal of Intangible Heritage.

Mori, M., & Dickens, P. (2012). History and techniques of the kimono. In: Adkins, Monty; Dickens, Pip. Shibusa: Extracting Beauty. Huddersfield, United Kingdom: University of Huddersfield Press, 2012: 117-134. University of Huddersfield Press. https://unipress.hud.ac.uk/plugins/books/7/chapter/62

Morris-Suzuki, T. (1992). Sericulture and the Origins of Japanese Industrialization. Technology and Culture, 33(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/3105810

NHK World [KIMONO SK Hollywood]. (2015, January 20). What is a Kimono? geisha, history, tradition, making process and trend now [HD] [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHwg7t9UeKM

Nishijin Woven Textiles. (2022). Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/nishijin-woven-textiles-art-research-center-ritsumeikan-university/bwXhyKJQOVlWJA?hl=en

Obradovic, P. (2021, December 2). A Sabukaru Introduction To The Kimono. Sabukaru. https://sabukaru.online/articles/modern-kimono-and-attitudes-towards-clothing-in-modern-japan

Polyzoidou, S. (2021, May 14). The Evolution of the Japanese Kimono: From Antiquity to Contemporary. TheCollector. https://www.thecollector.com/the-evolution-of-the-japanese-kimono/

Richard, N. N. (1990). Nō Motifs in the Decoration of a Mid-Edo Period Kosode. Metropolitan Museum Journal, 25, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.2307/1512899

Shively, D. H. (1964). Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 25, 123–164. https://doi.org/10.2307/2718340

The History of Japanese Kimono Clothing. (2019, November 13). Masterpieces of Japanese Culture. https://www.masterpiece-of-japanese-culture.com/traditional-clothing/history-traditional-japanese-clothing

The Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts, FUREAIKAN. (2022). The ancient history making and wearing a kimono. Google Arts & Culture. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-ancient-history-making-and-wearing-a-kimono-the-kyoto-museum-of-traditional-crafts/cAWBOL4nVSotIw?hl=en

Tsumugi, H. (2019, January 7). The size of a “tanmono”, kimono fabric. Hirota Tsumugi. https://archive.ph/20200704203011/https://hirotatsumugi.jp/blogen/post-5579

Ulak, J. T. (1992). Utamaro’s Views of Sericulture. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, 18(1), 73–103. https://doi.org/10.2307/4101579

Valk, J. (2018). Survival or success? The Kimono retail industry in contemporary Japan [PhD thesis]. University of Oxford.

Victoria and Albert Museum. (2016). Making Kimono. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/k/kimono-making-kimono/

Victoria and Albert Museum. Department of Textiles. (1919). Guide to the Japanese textiles v. 1. Printed under the authority of H. M. Stationery Off. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.5479/sil.96197.39088002297075

Appendix A

Illustrations of Transition from Kosode to Kimono

Source: Mori, M., & Dickens, P. (2012). History and techniques of the kimono. In: Adkins, Monty; Dickens, Pip. Shibusa: Extracting Beauty. Huddersfield, United Kingdom: University of Huddersfield Press, 2012: 117-134. University of Huddersfield Press. https://unipress.hud.ac.uk/plugins/books/7/chapter/62

Appendix B

An Image of Tanmono (roll of fabric) and How to Make Kimono from a Roll of Fabric

Source: The Kyoto Museum of Traditional Crafts. Kyoto, Japan

Appendix C

Diagram of the Manufacturing Flow of Kimono, from Creation to Retail (drawn by Takaharu Goto, owner of kimono shop Goto Gofuku)

Source: Valk, J. (2018). Survival or success? The Kimono retail industry in contemporary Japan [PhD thesis]. University of Oxford.

Appendix D

No 1. and 2. from the series “Women Engaged in the Sericulture Industry”

No 3. and 4. from the series “Women Engaged in the Sericulture Industry”

No 5. and 6. from the series “Women Engaged in the Sericulture Industry”

No 9., 11., and 12. from the series “Women Engaged in the Sericulture Industry”

Source: Kitagawa Utamaro's Joshoku kaiko tezcaza gusa (c. 1802), a set of twelve color woodblock prints featuring women at work in the various stages of the sericulture process, was acquired from Yamanaka and Company by Kate Buckingham in 1914, the year after her brother's death, and was given to The Art Institute of Chicago in 1925

Appendix E

A Collection of Pictures for Primary Instruction

Source: Kunmo Zu-i (A Collection of Pictures for Primary Instruction), Volume 10: Utensils (Kyoto, 1669-1695). Nakamura Tekisai, compiler. Eighteen of twenty volumes published by Yamagataya. 27 x 17 cm. (Ryerson Library 761.952 K961k)

Appendix F

Japanese Women Preparing Mulberries for Silkworms

Source: Preparing mulberry leaves to feed silkworms. (Yo-San-Fi-Rok: L’art d'élever les vers à soie au Japon par Ouekaki-Morikouni, trans. J. Hoffmann, annotated by M. Bonafous [Paris and Turin, 1848], pl. 16; courtesy of Tokyo National Museum.)

Appendix G

Itome gata yuzen: The outline of the base drawing is pasted on, using gum starch through a katagami stencil; it is the starch medium that is pasted onto the cloth.

Source: Mori, M., & Dickens, P. (2012). History and techniques of the kimono. In: Adkins, Monty; Dickens, Pip. Shibusa: Extracting Beauty. Huddersfield, United Kingdom: University of Huddersfield Press, 2012: 117-134. University of Huddersfield Press. https://unipress.hud.ac.uk/plugins/books/7/chapter/62

Appendix H

Hanagata-bon Design Showcasing Interpretation of Japanese Literature (Poem)

Source: "Kimono Designs" (Edo [Tokyo]: Yezoshiya Hachiyemon, and Kyoto: Yezoshiya Kisayemon, 1688 [Jokyo 8]). Title and artist not given. This is the second of a probable two-volume set. 25 sheets. 27 x 19 cm. (Ryerson Library 761.952 K49)

Appendix I

Hanagata-bon Design Showcasing Plum Motifs

Source: Hinagata Yado No Ume (Patterns: The Plum Tree of Our Home) (1730 [Kyoho i5]). Tagagi Kosuke, Banryuken, Manjiken Nakajima Tanjiro, Himekiya Magobei, artists. I volume, incomplete. 25.7 x i8.5 cm. (Ryerson Library 761.952 K866)

Appendix J

Modifications of Pine tree, Fan, and Paulownia Leaf Designs

Source: Moncho Zushiki Komoku (Book of Classified Forms of Crests) (Osaka: Aburaya Jinshichi, 1762 [Horeki 12]). Taga Kinsuke, artist. Murakami Kosuke, engraver. I volume, complete. Gift of Frederick W.

Appendix K

Hanagata-bon Design Showcasing Crane and Water Designs

Source: Hiinagata Kikunoi. Muto Ryusi, et al.(Picture). 27 cm x 19 cm. Woodblock printing. (Collection of Kyoto Institute, Library and Archives, formerly known as Kyoto Prefectural Library and Archives Production, photography by Horiuchi Color Archive Support Center)