Chinese Knotting: A Craft Weaving History, Symbolism and Artistry

Representing as an emblem of the Chinese national identity as seen at the Beijing Olympics 2022, Chinese knot is recognized beyond a decorative handicraft, but a folk art that intertwines craft and identity.

Often adorning Chinese homes and temples during festive occasions with its many elaborate designs and a signature deep red to express good wishes and ward off evils, Chinese knotting (中国结 zhōngguó jié) is a distinctive and traditional form of decorative folk handicraft. The term “knot” is defined as “the joining of two cords” in Shuowen Jiezi (around CE 100), the first comprehensive Chinese character dictionary (Chen 4). Over the course of history, the craft transformed and developed into a multitude of variants and served different purposes, substantially integrating itself to the everyday life of Chinese people and positioning itself as a highly regarded art form.

Despite its importance, Chinese knots have traditionally played a rather secondary role in the decorative arts as they are often employed to enhance the beauty of other dominant art pieces. For instance, knots appear as a pattern or charm on traditional costumes, furnitures, and more. Therefore, their importance has easily become unrecognized, resulting in poor record keeping and, in turn, scarce documentations on the craft, its practice and culture.

With this project, I aim to study craft biography from literatures and practice through a hands-on approach by making the knots. Additionally, I will reflect on the experience of learning Chinese knot as a beginner as an attempt to pose commentary on the transfer of knowledge of the craft.

History

The art of tying knots dates back to prehistoric times, with the first clue of the earliest knots found with the cultural relics of bone needles, pierced shells and dyed stone beads in the late Paleolithic period of some 18,000 years ago. Before their decorative needs, knots are mainly used for utilitarian purposes, such as for record keeping. As documented in a chapter in the classic Chuang-Tzu, a foundational text of Taoism, the practice of tying knots to keep a record of events was employed until the invention of writing which replaced this purpose, where big knots represented great events whereas smaller knots signified events of less importance (Chen 90).

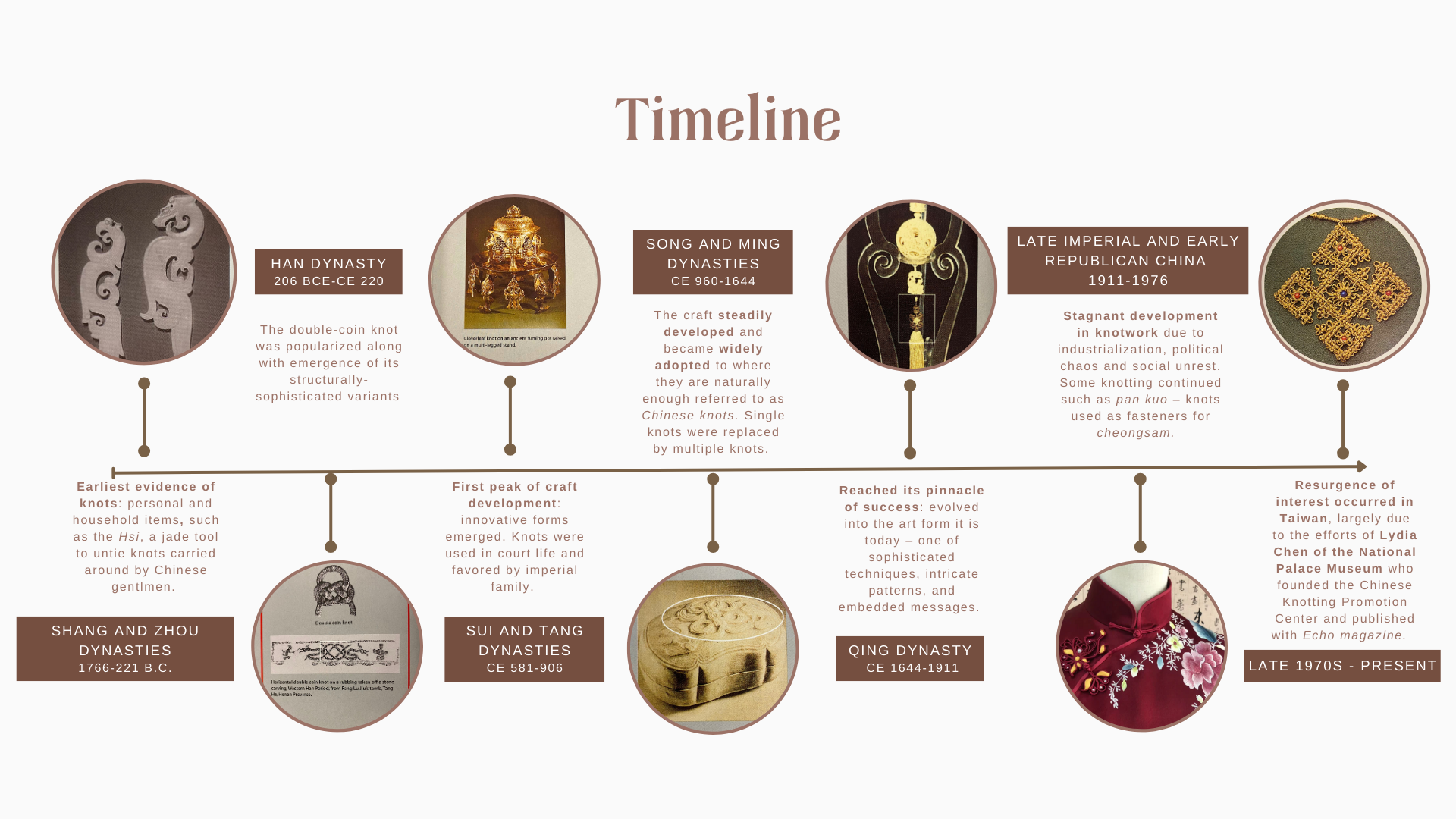

Besides serving as a communication medium in ancient times, knots functioned as practical tools as well as acted as decorative, symbolic emblems in ritual practices. For instance, the double-coin knot is often associated with blessing for an everlasting love. With knots often appearing as supportive ornaments to the dominant, the poorly documented craft relies on other sources for possible references to gain insights on knotwork from its looks to its techniques, from poetry, painting, carving, furniture to clothing accessories. Through these multi-materia vessels, the timeline of the development of Chinese knotwork was unveiled as summarized and illustrated below.

Images Source: Chen, Lydia. The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting: A Compendium of Techniques and Variations. Tuttle Publishing, 2018. Illustrated by Angel Truong.

Chinese Knotting and Its Characteristics

As the craft developed over the course of history, Chinese knotting also assumed a catalytic role in the development of the art of knotting in both Korean Maedeup and Japan Mizuhiki. Comparatively with its neighboring cousins, Chen classified Chinese knotwork with the following characteristics:

Very compact in structure

Highly decorative

High structural complexity with many pattern variations

Symmetrical in form

Three-dimensional: consist of two layers of cord with an empty space in between

In regards to the craft and its technical maturity, the closest knotting culture is Korean Maedeup, whereas the Japanese Mizuhiki, practice of decorating gifts and envelopes with decorative cords, remains rather confined in application exclusively to gift wrapping. Since the Japanese knotting found its origin from the practice in the Tang dynasty of typing gifts with red and white strings, it comparatively demonstrated no innovative breakthrough with simple knots in form and relatively loose in structure (Chen 90-91).

On the hand, Korean knotting dates back to the Three Kingdoms period (37 B.C.-A.D. 668) where it began to be used beyond for decorative purposes, such as talismans for good blessings, decorations in the royal court for Buddhist-related ceremonies and paintings, and finishing touches to scrolls, musical instruments and more (Kim 9). During the Joseon era (1392-1910), maedup became widely used and began to emerge as an element of high social status, signifying dignity and prestige (Velazquez). Over the course of history, the Korean knotting culture has been able to uniquely developed and retain their own craft aesthetics, possessing the following characteristics that differentiated themself from their Chinese origin (Lee):

Bilaterial symmetry knot with a tassel (sul) at the bottom of the knot

Relatively tighter knots

Not often flat or pattern-based (like other knots across Northeast Asia)

Plain and reserved beauty

Subtle but rich colors

Besides structural diversity and versatility in application, Chinese knotwork interweaves itself to the people’s life and culture, tangible and intangible. Chen highlighted knotwork as a decorative art, evidently with all the cultural relics, and as a symbolic icon (Chen 94-97). As a matter of fact, knots are named according to specific shapes, usages, meanings, for instance the Button Knot functions as a button, or the Auspicious knot (also known as “seven-circle knot”) symbolizes good luck, peace, and prosperity (International Department of Central Committee of CPC). As the knots embody meanings, the craft transcend beyond a supplementary, decorative ornaments, but a craft itself. Thus, my project seeks to study this beauty folk art of expansive influence.

My Reconstruction of Craft & Reflection

About the author and primary source

My craft biography research and reconstruction project center on the textbook The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting: A Compendium of Techniques and Variations by Lydia Chen, the a renowned authority in the Chinese knotting scene.

Being involved in the knotting research for nearly a century, Chen’s initial exposure to traditional knotting culture was influenced by her father-in-law, Chuang Yen, who was a vice director at the National Palace Museum, and learnt the craft from Wang Zhen-kai, a skilled craftsman. Later, she worked at the National Palace Museum and had the opportunity to study various Chinese knotting techniques from different time periods for over half a century. Integrating knotting with other art forms, she added more breakthroughs to her creations by playing with forms, materials and functions, such as lacquer knotting and metal knotting (Asia Trend).

Lydia Chen is a well-known knotting artist, recognized for breaking from the traditional knotting techniques and experimenting with design and materials.

The revival and preservation of Chinese knotting, especially in Taiwan, in the modern era is attributed to her.

The primary source entails a section introducing the craft and provides step-by-step instructions with visual illustrations on recreating both basic and compound knots. The text introduced fourteen basic Chinese knots and four main techniques to tie them, which include (1) pulling and wrapping outer loops, (2) using single flat knots, (3) over-lapping outer loops and (4) knotting semi-outer loops or “S” curves (Chen 18). These basic knots have numerous permutations, either from variations of the originals or from a combination of basic knots, by performing nine ways of modifying basic designs (Chen 20).

By solely relying on the textbook to expose myself to the craft and learn its techniques, I will be able to comment on the opportunities and challenges associated with this indirect, text-based transfer of knowledge from a seasoned knotting artist to a beginner.

Craft Reconstruction: My Attempt at Chinese Knotting

With just the instruction book and my satin cords ordered from Amazon, I decided to begin my reconstruction journey, thinking that is all the materials I need. For the reconstruction process, I decided to follow the manuscript and remake Cloverleaf knot, Double-Coin knot, and Pan chang knot, as they are three of the basic, commonly-used knots.

It took a little learning curve to work with the instructions on how to create the knots and working with the cord, but I soon was able to follow through and produced the Cloverleaf knot and Double-Coin knot. However, the process got challenging when I got to the Pan Chang knot. I quickly realized just the instructions and illustrations from the book is not enough.

Images source: https://artsproutsart.com/chinese-knots-how-to-chinese-new-year-traditional-craft/

After multiple failed attempts at different types of knots, I consulted a secondary source that I also used in the beginning to decide on the materials given that the text book mentions nothing on the materials needed to get started on the craft. Ringing up a neighbor friend, I also acquired some pins. My decision looking for pins came from recalling a source that referenced the need for a macrame board and from me consulting a youtube video on knotting. Moving forth, I continued with more materials acquired and weaved the following knots.

Reflection on the Reconstruction Journey

During my reconstruction journey, there was an aha moment when I was learning to knot the Strap Knot and the Plafond Knot (as pictured above). These two knots share the same step 2, which was where I initially stumbled. The instruction given step 2 is not clear enough, because it does not elaborated on how and in what way should the knot be pulled to tighten horizontally. After several attempts of tying and untying, I figured out that the inner loop needs to be pulled out horizontally between the top and bottom cord on two sides. After my successful attempt with the Strap Knot, I applied my new knowledge on the Plafond knot. This experience makes me reflect on how craft knowledge is transmitted, and it raises the question of whether, even when aimed at a general audience, the artist unintentionally conveys it in a way that relies on tacit understanding. For instance, the text mentioned nothing of the materials (i.e.: type of string/cord to be used, knotting board, pins etc.), the optimal string length (generally or specifically to a particular knots) or best practices in knotting.

As I ventured to attempt at the compound knots, I faced many challenges to following the instructions and began recognizing areas with missing or unclear craft knowledge. To my disappointment, I was unable to produce any of the compound knots that I initially set out to do. Reflecting on my attempt to learn the craft as a beginner, I would attribute my struggle to the aforementioned lack of information and hands-on mentorship. Knowing that the craft was traditionally preserved and passed down by word of mouth and apprenticeship, I recognized the knowledge gap now that the craft knowledge is transmitted through an instruction book is rather disconnected and indirect.

Furthermore, Chen applied her background in science and engineering to present various knotting techniques in her books using geometric algebraic formulas (Ministry of Culture). This interesting approach blurs the conventional dividing line between traditional craft and science. It also that raises the question of how differently the craft was conceptualized and knowledge mobilized in pre-modern versus modern times.

Final Thoughts

Through my research on the craft of knotting across East Asia, extensively on Chinese and Korean knotting because of their similarity in technical maturity, I found that both traditional Chinese and Korean knotting scenes experienced a period of prolonged dormancy due to industrialization, modernization, and Western influence.

As the 20th century progressed, the Korean knotting culture experienced a decline in interest and demand for maedeup and dahoe (braided strings for knotting) as Koreans increasingly adopting Western-style clothing as well as the introduction of machines for plaiting dahoe. Until the 1960s, the Korean government pushed for a resurgence in the practice by designating the craft National Intangible Cultural Heritage No. 22 to preserve and promote the traditional craft (Korea.net).

Similarly, as the nation took a turn to rapidly industrialize and modernize, Chinese knotting culture was almost forgotten in the past as just another outdated practice until its revival by artists widely spreading the knowledge of the art.

Thus, amid the surplus of product alternatives and the continuous aging of traditional folk arts, the reconstruction journey makes me wonder the following broad questions, which I will attempt to pose my thoughts while extending the discussion to the readers (you).

Which type of craft can afford transformation whether that be in its practices or its process of knowledge transfer to withstand social changes and survive time?

Unlike the traditional methods of knowledge transfer by word of mouth or apprenticeship, knotting culture survived because it is now documented and logistically-convenient to spread in the form of instruction books. Therefore, my guess would be that the craft would have to possess characteristics of being easily recorded and accessible (in terms of materials and spacial need). Furthermore, the craft would need external supports, such as government preservation projects.

What are the gains and loses of popularizing a craft to a larger community of practitioner/audience?

Evident with the cases of Korean and Chinese knotting, I understand that the possible gains would be gaining a wider audience, which in turn can translate to more appreciation, preservation of craft, and accessibility to the practice.

On the other hand, I would pause to question whether such popularization, perhaps arguable commercialization of the craft, would lead to dilution of tradition and losing meanings (a craft turns to simply a product).

Sources

Asia Trend. “Cultural Features: Knotting Artist | Lydia Chen.” November 20, 2023. https://asiatrend.org/arts/cultural-features%EF%BC%9Aknotting-artist-lydia-chen/

Chen, Lydia. The Complete Book of Chinese Knotting: A Compendium of Techniques and Variations. Tuttle Publishing, 2018.

Chen, Lydia H.S. “Chapter 6 The art of Chinese knotwork: A short history.” History And Science Of Knots (1996): 89-106. https://books.google.com/books?id=ovDsCgAAQBAJ&lpg=PA89&dq=chinese%20knotting&lr&pg=PA105#v=onepage&q=chinese%20knotting&f=true

Esaulov, Vladimir. “Data Storage with Knots and Beads.” Kochi Arts & Science Space. July 20, 2018. https://kartsci.org/kocomu/computer-history/data-storage-knots/

International Department of Central Committee of CPC. “Chinese Knots.” https://www.idcpc.org.cn/english2023/chinadelights/arts/crafts/202307/t20230727_157739.html

Lee, Eun-yi. “Maedeup, Just Enough in Every Way.” Korean Culture and Information Service (KOCIS). August, 2018. https://www.kocis.go.kr/eng/webzine/201808/sub06.html#

Ministry of Culture. “Knotting Artist | Lydia Chen.” Artisans & Craft Makers. September, 2023. https://www.moc.gov.tw/en/News_Content2.aspx?n=486&s=173825

Kim, Hee-jin. “Maedeup The Art of Traditional Korean Knots.” Korean Culture Series 6. Hollym, 2017.

Korea. net “[Exhibition] Maedeup, Korean Knots” Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. https://www.korea.net/Events/Overseas/view?articleId=20986#:~:text=Notably%2C%20the%20Joseon%20royal%20family,as%20a%20craft%20and%20occupation.

Velazquez, Laura Lopez. “Knot dying out: traditional craft of maedeup.“ Korea.net. Jan 23, 2021. https://www.korea.net/NewsFocus/HonoraryReporters/view?articleId=193837