Against the Grain: Chinese Rice Wine from the Qimin Yaoshu

Qimin Yaoshu (a printed Ming Dynasty edition)

Introduction

Alcohol is an important part of social culture. It is present in ancient art, with wine vessels being a popular medium displayed in museums, and alcoholic imagery depicted in the paintings of nearly every civilization. While there was independent development of alcohol production practice, trade allowed for the transmission of information far and wide across Eurasia. In modern times, we generally perceive alcohol through its consumption rather than its production. That is because most of today’s alcohol is mass-produced with machinery in breweries and even in the very natural settings of vineyards. However, there is a long history of alcohol production, especially in East Asia, with its origins as far back as 7000 BCE. While China has popular alcohols such as its Tsingtao Beer and varieties of Baijiu liquor like Maotai, sake and soju have become extremely popular and have elevated Japan and Korea to positions as well-known alcohol producers in East Asia. In the West, soju’s popularity has aided Hallyu, also known as “the Korean Wave”, in bringing Korean culture to Western audiences. Similarly, sake and Japanese whiskey have become highly prized by Western connoisseurs. Chinese alcohol, on the other hand, has reached the West to a lesser degree, even though its roots extend back further than those of Korean and Japanese alcohol. Therefore, when compared with alcohol in Korea and Japan, the presence of alcohol in China has been largely minimized.

The history of Chinese alcohol has also been overshadowed by the discourse of alcohol in Europe. According to Li and Wang, “publications such as ‘The World Atlas of Wine’ claimed that the wine-producing countries could be divided into two worlds: ‘Old World’ and ‘New World’” (Li and Wang). However, the French Foreign Trade Advisory Committee (CNCCEF) considers China to be part of the “New New World”, which includes “the latest countries producing significant quantities of wine.” Li and Wang argue that “winemaking technology and wine culture are rooted in Chinese history, and the definition of ‘New New World’ is a misnomer that imparts a Eurocentric bias onto wine history and ignores fact.” The fact is that China’s alcoholic production has existed since the Neolithic Age, way before there was any concept of a “Europe”. The primary source of my rework project, the Qimin Yaoshu, reflects this history of Chinese alcohol culture, as it contains 40 different wine recipes.

During the Wei, Jin, and the Southern and Northern Dynasties (220-581 CE), which was when the Qimin Yaoshu was written, the “development of winemaking technology and the formation of wine culture” occurred (Li and Wang). And in the following Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE), there was a “blossoming of wine culture.” Although Li and Wang’s overview focuses on grape wine, rice wine has even older roots and the development of grape wine culture most likely included rice wine as well. Thus, the Qimin Yaoshu’s writing reflects and possibly contributed to the growing popularity of wine culture in China.

My rework project is based on a recipe from the Qimin Yaoshu. The Qimin Yaoshu is an encyclopedia written by Jia Sixie, a government official and farmer, during China’s Northern Wei Dynasty (c. 540 CE). The title translates to “Essential Techniques for the Welfare of the People,” and is comprised of 10 volumes and 92 chapters of technical information about agriculture and 280 culinary recipes. He uses a “plain, precise technical language…rooted in the vernacular” (Bray), which keeps recipes short and straight to the point. It quotes almost 200 other ancient sources and was widely distributed throughout China and overseas. In fact, in the late 19th century, Charles Darwin cited the Qimin Yaoshu in the famous On The Origin of Species, referring to it as “an ancient Chinese encyclopedia” (Nature).

The preface of the Qimin Yaoshu is as follows:

“I have made excerpts from classics, contemporary books, proverbs and folksongs, gathered information from experts, and drawn from personal experience. Beginning with ploughing and cultivation, down to the making of vinegar and meatpastes, any art useful in supporting the daily life (of the common folk) is jotted down.”

Recipe

Method for Brewing Melon-Pickle Wine (from Volume 8 of the Qimin Yaoshu)

秫稻米一石: One shi (石, ancient volume unit) of glutinous rice.

麥麴成剉隆隆二斗: Two dou (斗, ancient volume unit) of wheat qu (麴, fermentation starter/mold), coarsely chopped.

女麴成剉平一斗: One dou (斗, ancient volume unit) of "female" qu (麴, fermentation starter/mold), finely chopped.

釀法湏消化: The brewing method must involve thorough fermentation.

復以五升米酘之: Add five sheng (升, ancient volume unit) of rice again.

消化復以五升米酘之: Ferment, then add another five sheng (升, ancient volume unit) of rice again.

再酘酒熟則用: Ferment again. When the wine is ready, use it.

不迮出𤓰鹽揩: Do not rush to take it out. Use salt to rub the gourd.

日中曝令皺鹽和暴糟中: Expose it to the sun to let it wrinkle; mix the salt with the leftover mash.

停三宿度內女麴酒中為佳: Let it sit for three nights; adding "female" qu to the wine within this period is best.

(translated from Generative AI)

Questions

As I struggled to follow Jia’s recipe and researched how to go about filling the knowledge gaps, two research questions came to mind:

What do Jia’s extremely brief, yet technical, instructions demonstrate about winemaking culture in China during this time?

How might a modern audience struggle to follow the recipe compared to Jia’s audience in China during the Northern Wei period?

Ingredients: Sweet Rice, Barley (wheat qu), Dried Yeast (female qu), Sorghum (for backup)

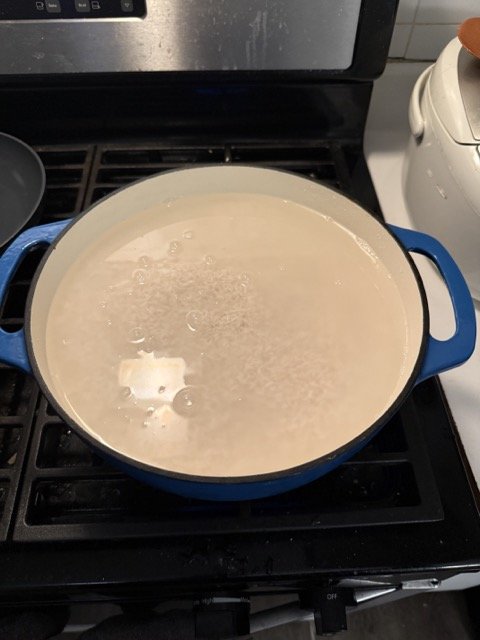

First, I steamed rice in the biggest pot I could find and then I let it cool.

Next, I crushed the yeast and mixed

it with barley and water to make the fermentation starter.

Fermentation Starter: Yeast, Barley, and Water

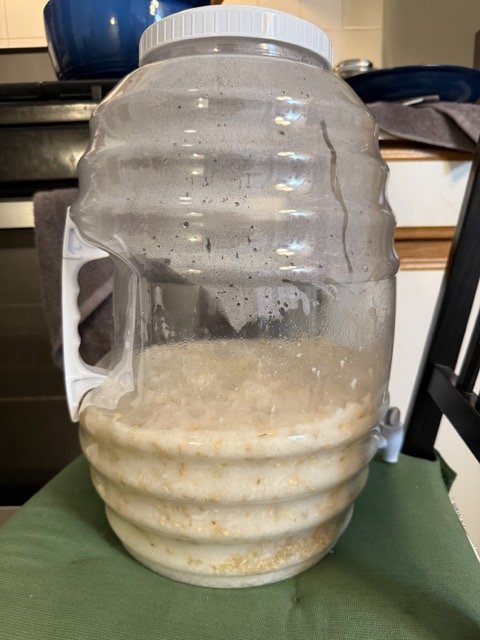

Then, I mixed the rice with the fermentation starter inside an airtight container and stirred it well. I made sure to stir it well because, for fermentation to work, the yeast must attach to the rice for the starches in the rice to convert into alcohol.

I made sure to use an airtight container to protect the mixture from unwanted contamination.

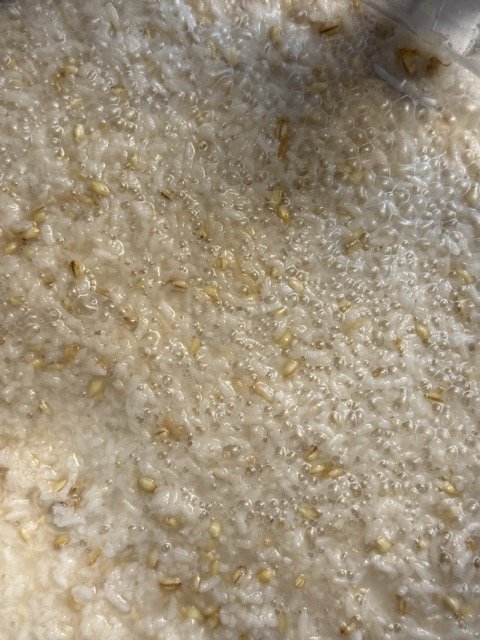

I stirred the mixture every day for three days, and it started to bubble on the second day. Stirring it led to more bubbles and produced a foaming sound similar to the sound of a bubble bath.

Substitutions/Justifications

First off, the recipe calls for 1 shi of rice, which is equal to 100 liters, a massive amount of rice. I did not have the capacity or the materials to make this much rice wine, so I used 2.8 liters of rice instead. Thus, I scaled all of the other ingredients down to 2.8% of their original amounts, and even then, it still feels like a large serving of alcohol. Perhaps with the original measurements, the yeast activation might have been more effective, but I am not entirely sure.

Because Jia’s recipe was not very specific about the ingredients, other than to use glutinous rice, I had to use what I could find at the supermarket. Therefore, I used barley grain as the wheat yeast and regular yeast as the female yeast. Barley is a grain commonly used in China, so I felt like it was sufficient as a substitution for the wheat yeast. However, I did not know how well it would work as a yeast, but I felt like the yeast I bought could aid the barley. I could not figure out what Jia Sixie meant by “female yeast,” so I just used regular yeast I found at the supermarket. It seems that these substitutions worked well as fermentation successfully started.

My unfamiliarity with alcohol-making, coupled with the vagueness of the recipe, made me inclined to use outside help from recipes and videos of alcohol production on the Internet. I specifically watched rice wine videos for products like makgeolli and sake, and took some of their advice into account. For example, I added water to the fermentation starter because it is supposed to create a nutrient-rich environment for the yeast to thrive, and it is supposed to help the taste of the product.

Main Obstacle

One important piece of information Jia left out of this recipe was the fermentation process for this wine. He simply tells the reader to ferment it, add more rice, and then ferment it again. What should the winemaker look for to know when the wine is done fermenting? Is there an approximate number of days for which to ferment it?

Comparison with an English Survey of Qimin Yaoshu

At the time I began the process of reworking the rice wine recipe, I did not have access to a credible English translation of the Qimin Yaoshu. However, I was eventually able to obtain a copy of A Preliminary Survey of the Book Chʻi Min Yao Shu, written by Shenghan Shi in 1962. This work provides an analysis of the Qimin Yaoshu and explains more about the techniques for making the different recipes. In the alcohol and fermentation section, I found an explanation of what Jia Sixie would have expected the fermentation process to look like.

Shi explains that the fermentation starter should be a “well-steamed cereal-corn and clean [with] sweet fresh water.” My fermentation starter matches well with this, since I used barley, yeast, and water.

There is also further instruction on what the fermentation starter should look like:

“When such a ‘meal’ is cooled down to an appropriate temperature and shaped into pieces of convenient size, these ‘cakes’ are moved into a darkened chamber of fairly constant humidity and temperature. After being kept there for 3 weeks with occasional turning over (to equalize the conditions of humidity, temperature and aeration), the ‘cakes’ will be well matured. They are then taken out, dried in the sun, and hung up in strings. These ‘starters’ are thus ready for use, and can be kept for at least 3 years.”

There was also “emphasis laid on the darkened and ‘air-tight’ conditions of the starter chamber” as the “absence of light favours the germination and development of intercepted spores of the fermentative microorganisms.” Even though I am keeping my rice wine in an airtight container in a dark room with minimal light, these instructions are for the fermentation starter, which, according to the survey, should be kept for three weeks.

Analysis

My struggle with this recipe from the Qimin Yaoshu lies in the lack of specificity and direction that Jia provides. Bray mentions how the treatise “specifies which implement to use for which operation, but provides no information about the construction of farm tools or machinery” (Bray). It was also “composed before printing was available and makes no use of graphics,” making it harder to follow along.

It is important to note Jia Sixie’s audience, though. According to Bray, “the scale of Jia’s calculations suggests that his treatise was intended for owners of large estates combining subsistence production with commerce” (Bray). This makes sense as to why 1 shi or 100 liters of rice was used for this recipe. It also explains why so much information was omitted on how to brew the alcohol, since Jia’s audience was made up of other farmers and landowners who were familiar with alcohol production.

If this familiarity was widespread, Jia’s omission points to the existence of a culture of alcohol production and consumption in China that had been embedded in China long enough to not include details on the fermentation process and guidance on time.

Conclusion

In Hyunhee Park’s book on the history of soju, she explains how “previous studies of distillation’s history focused mainly on Europe; one authority even regarded distillation as a thoroughly European invention that disseminated to other cultures after its invention,” but that “studies like Joseph Needham’s celebrated volumes Science and Civilisation in China, which demonstrate Asia’s early knowledge of distillation technology…have rendered such a view inappropriate and laid the foundations for current global and world-historical approaches” (Park). If we see this dismantling of Eurocentric alcohol research occurring with the research of distilled liquors, perhaps research and reconstruction of alcohol recipes in the Qimin Yaoshu can have a similar impact.

Works Cited:

Bray, Francesca. “Thinking with Diagrams: The Chaîne Opératoire and the Transmission of Technical Knowledge in Chinese Agricultural Texts.” East Asian Science, Technology and Society, vol. 14, no. 2, 2020, pp. 199–223, https://doi.org/10.1215/18752160-8538106.

Jia, Sixie. Qimin Yaoshu. Translated by Donald Sturgeon, Chinese Text Project, ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=en&chapter=75594. Accessed 2 Apr. 2025.

Li, Hua and Hua Wang. Overview of Wine in China. EDP Sciences & Science Press, 2022. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=3555258&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Park, Hyunhee. Soju: A Global History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021. Print. Asian Connections.

Shi, Shenghan. A Preliminary Survey of the Book Chʻi Min Yao Shu : An Agricultural Encyclopaedia of the 6th Century. 2d ed., Science Press : distributed by Guozi Shudian, 1962.

A Chinese renaissance. Nature Plants 3, 17006 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.6